It was like being transported into this parallel universe where everything functioned in a haphazard way.

The first day at my Uncle’s house in Lagos the lights went off and everybody screamed NEPA. I asked who NEPA was. My Uncle laughed. NEPA; short for the National Electricity and Power Authority, was supposed to supply electricity but rarely did. Despite Nigeria’s famous oil reserves, the power would routinely switch off in the middle of using the electric cooker, ironing or watching football and you would hear the collective cry from the neighbours as people would shout and issue curses as if NEPA was a human, who turned the electricity on and off at whim

The rich and middle class Lagosians had generators. My father’s younger brother was an accountant but out of principle he refused to buy a generator because he said they were a symbol of all the things that were wrong about Nigeria. His wife was always nagging him to buy a generator because she couldn’t keep anything perishable in the fridge like meat or fish.

One day I read in the newspapers that a family of six had died after inhaling the fumes from a generator left on overnight. That was just everyday Lagos. People would gather around and talk about how horrible it was and then they would switch on their generators and go to bed and pray that God would take care of them.

Normal for me was cold and wet London. It was eating fish and chips dripping with vinegar wrapped up in newspaper and rushing home on Friday to watch East Enders. It was watching your breath turn to icy smoke as you stood in front of the bus top and agreed with the old dear who shook her head when you said – “Terrible weather innit.”

It was normal that we both find agreement in the weather even though we had never met before. It was normal that I would turn and comment on her dog and say how nice it was – even if it was mangy had fleas and a bad attitude.

That was the normal I knew. The normal I craved.

There was so much to learn about the country of my parents and every time I asked questions, people would answer with another question.

Why do you ask so many questions?

Why are you not married yet?

Why don’t you get this job/ drive this car/ live here or wear this.

People would just laugh and I found it uncomfortable. They laughed when I spoke; when I asked why everyone seemed so scared of policemen, why there were so many children selling things on the roadside when they should be in school or why any man needed to have more than one wife.

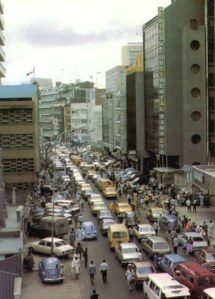

Despite the terrible roads, the dire transportation system and the sometimes shaky political situation, people seemed to be relatively happy.

No matter how bad it got – I understood that optimism was ingrained into the Nigerian DNA. You could see it everywhere in the children that walked miles to school chattering away happily, in the buses and lorries bearing slogans such as words ‘God Dey’ another with, ‘Only God can judge me’ and, ‘God will bless me’.

I soon learnt to respect the resourcefulness of Nigerians. Commerce in this city is not 9-5! It was in Lagos that I went to my first night market. The night was a black velvet backdrop scattered with the lights of thousands of kerosene lamps flickering from the market stalls, where women sat frying puff–puff and chin-chin.

I couldn’t believe it, despite the blackout life went on. Was their nothing Nigerians could not adjust themselves to? Coups, blackouts, hunger, poverty, fuel shortage….the atrocious cost of tomatoes!

I thought of my uncle’s resilience. He reminds me of a Nigerian version of Del Trotter. He always believes like so many other Nigerians that ‘Tomorrow go better.” I must confess that I did not always share his optimism.